Issues with international travel in Europe and between Europe and the rest of the world

Epidemiological situation

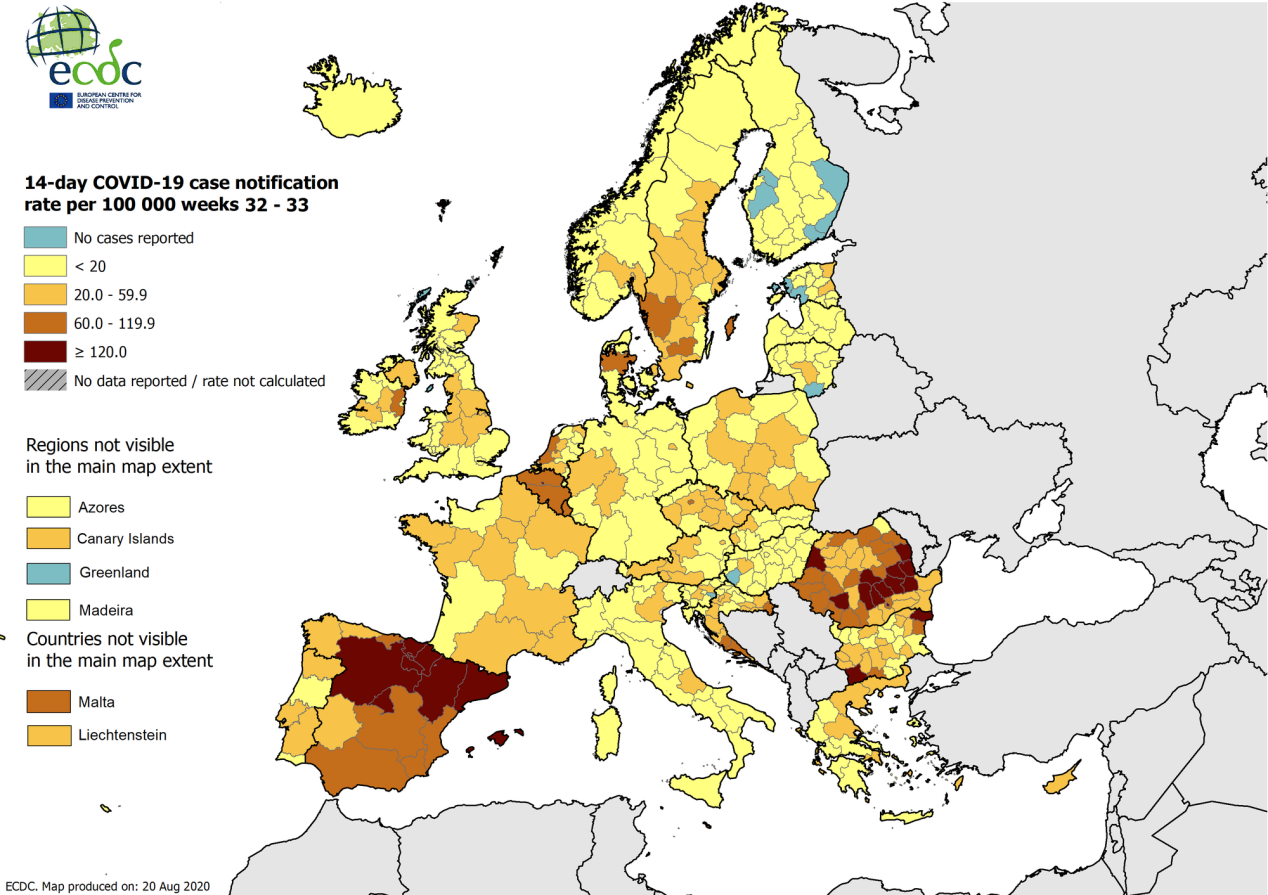

Different (European) countries are in differing epidemic states, as is clear from the below map (Source: https://www.ecdc.europa.eu/en/cases-2019-ncov-eueea) :

Virus circulation is low in Germany, Slovenia, Slovakia, Norway, Italy, Lithuania, Estonia, Finland, Hungary, Latvia. It is very high in Spain, and high in Malta, Luxembourg, Romania, France, Croatia, Belgium, the Netherlands, as can be seen from the below table. Of course, we have to take into account that different countries have different test strategies, hampering comparison a bit.

(same ECDC source; also reproduced in daily Sciensano update):

| Country | Total confirmed cases | Total deaths | Confirmed cases over the last 14 days | 14-day incidence |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Spain | 386 054 | 28 838 | 71 692 | 153 |

| Malta | 1 577 | 10 | 598 | 121 |

| Luxembourg | 7 704 | 124 | 591 | 96 |

| Romania | 77 544 | 3 233 | 16 921 | 87 |

| France | 238 002 | 30 512 | 40 081 | 60 |

| Croatia | 7 900 | 170 | 2 357 | 58 |

| Belgium | 81 374 | 9 988 | 6 436 | 56 |

| Netherlands | 66 034 | 6 191 | 8 047 | 47 |

| Sweden | 86 068 | 5 810 | 3 745 | 37 |

| Austria | 25 099 | 732 | 3 164 | 36 |

| Czechia | 21 790 | 411 | 3 555 | 33 |

| Liechtenstein | 101 | 1 | 12 | 31 |

| Denmark | 16 127 | 621 | 1 685 | 29 |

| Iceland | 2 058 | 10 | 103 | 29 |

| Greece | 8 381 | 240 | 2 960 | 28 |

| Poland | 61 181 | 1 951 | 10 014 | 26 |

| Portugal | 55 211 | 1 792 | 2 674 | 26 |

| Ireland | 27 908 | 1 777 | 1 264 | 26 |

| Bulgaria | 15 131 | 539 | 1 788 | 26 |

| United Kingdom | 324 601 | 41 423 | 14 838 | 22 |

| Cyprus | 1 417 | 21 | 184 | 21 |

| Germany | 232 864 | 9 269 | 16 239 | 20 |

| Slovenia | 2 617 | 127 | 370 | 18 |

| Slovakia | 3 316 | 33 | 750 | 14 |

| Norway | 10 197 | 264 | 729 | 14 |

| Italy | 258 136 | 35 430 | 8 033 | 13 |

| Lithuania | 2 594 | 84 | 363 | 13 |

| Estonia | 2 265 | 63 | 118 | 9 |

| Finland | 7 871 | 334 | 303 | 5 |

| Hungary | 5 133 | 611 | 480 | 5 |

| Latvia | 1 333 | 33 | 45 | 2 |

Countries all over the world show a large heterogeneity in (a) viral circulation (as measured by 14-day incidence, for example), and (b) evolution (increasing, steady-state, decreasing).

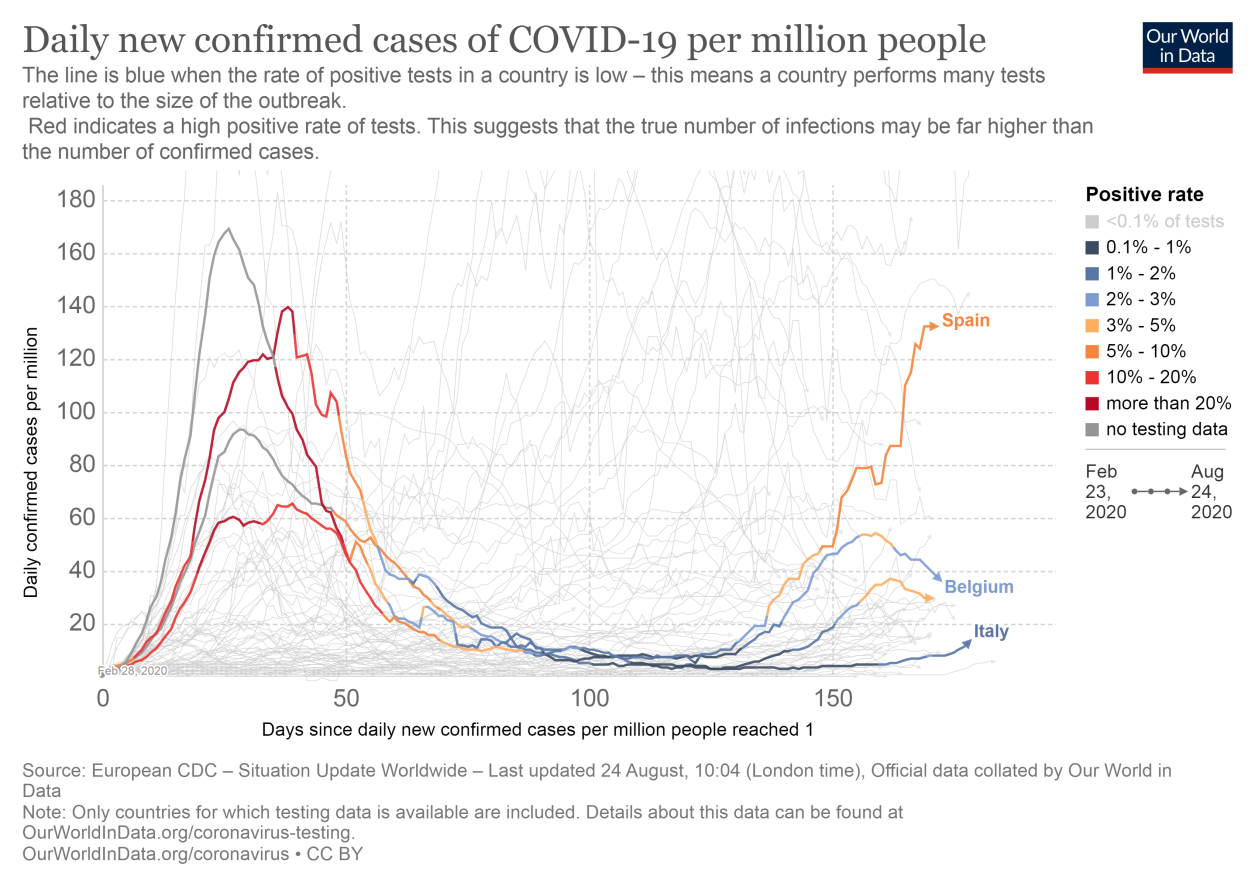

Let us consider Belgium against Spain, Italy, and the Netherlands in terms of daily new cases per million, as presented in Oxford’s “Our World in Data.” The difference between Spain and Italy, both Mediterranean countries, is striking. Currently, Spain’s incidence is more than 10 times higher than Italy’s, as can be seen in the above table.

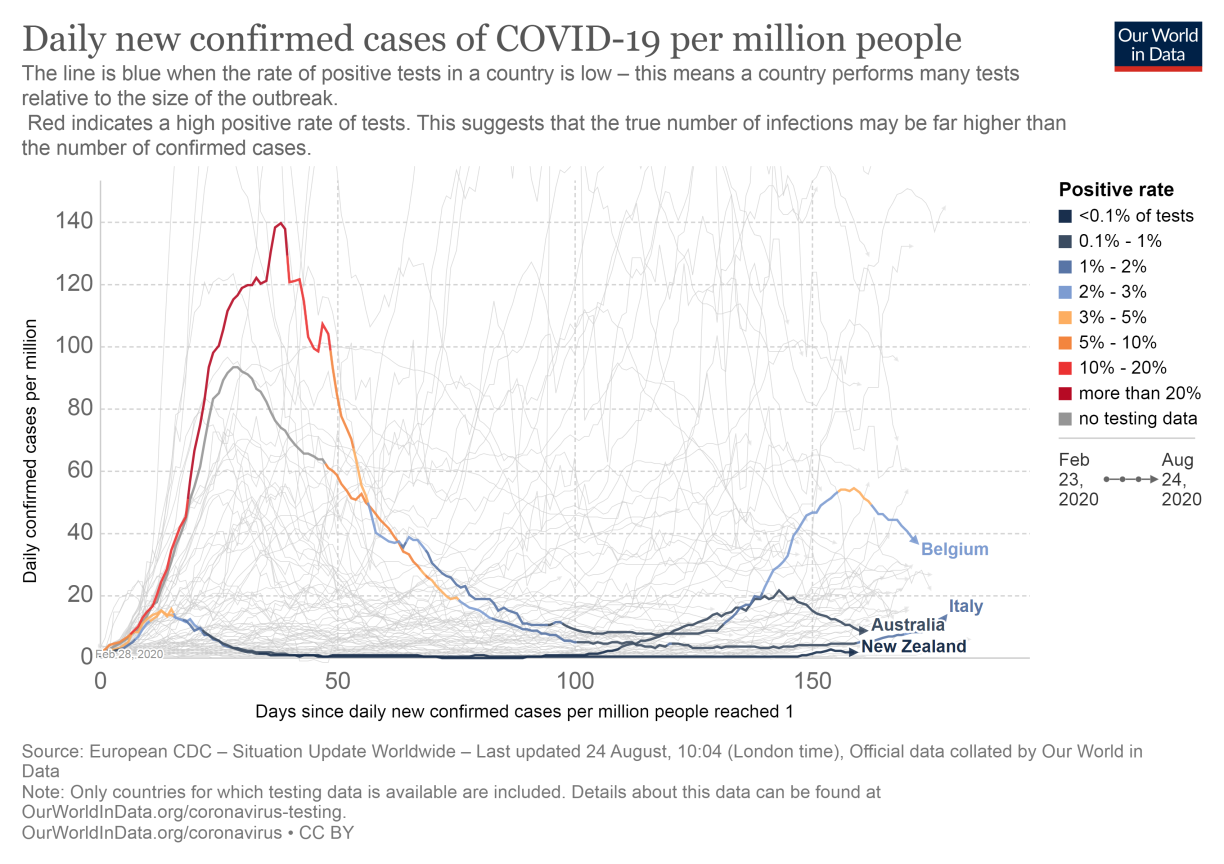

If we consider Belgium against the background of Italy, Australia, and New Zealand, the difference is, once again, striking.

Italy had a large first peak, but has maintained low incidence levels throughout the summer. It is an interesting case in that sense: after a severe epidemic situation in March-April-May 2020, it has been able to crush the curve until now. Note also that in some regions background immunity can be relatively high in some regions at this time, hampering or at least slowing virus circulation.

It has been taken unusually strong measures:

http://www.salute.gov.it/portale/nuovocoronavirus/dettaglioFaqNuovoCoronavirus.jsp?lingua=english&id=230#11

Note that these measures include indiscriminate use of face-mouth masks, except during night time. Note also that the measures have recently been tightened a bit, because the incidence as slightly increased (from 7 to 13 over a period of about a week). So, Italy quickly reacts to any unfavorable trend in the curve).

In contrast to Italy, as we all know, Belgium did show a rise but is fortunately showing a decline.

Australia and New Zealand, admittedly island countries, never had more than a local bump in the first peak. This is the case for several other countries as well. A non-exhaustive list: Norway, Finland, Taiwan, South Korea, Vietnam, Thailand, Georgia, China (outside of Hubei), etc.

These countries have chosen the route of suppression (popular name: crush the curve), rather than mitigation (popular name: flatten the curve). A successful route to this end:

- Quick, and at first sight out-of-proportion reaction as soon as there is viral circulation.

- Closure of borders, between countries, but also interior borders (example: state borders of Victoria and New South Wales, at first signs of outbreak in Melbourne)

- National fight against the virus, targeted communication

- Non-pharmaceutical intervention of a stable nature (e.g., face masks in Italy)

- Efficient testing, tracing, and isolation policy.

- With the help of low population density in some of these countries

In Europe and beyond, we see that a group of countries is emerging with a successful suppression strategy.

These include:

- EU member states: e.g., Germany, Slovenia, Slovakia, Norway, Italy, Lithuania, Estonia, Finland, Hungary, Latvia, etc.

- Other European countries: e.g., Georgia (our Ambassador indicates that Georgia’s situation is excellent, in spite of the presence of several severely affected countries in the region, including Iran).

- Non-European countries: e.g., China, South Korea, Australia, New Zealand, Thailand, Vietnam, etc.

Based on information and analyses by the German Robert Koch Institute, which reached us on (https://www.rki.de/DE/Content/InfAZ/N/Neuartiges_Coronavirus/Risikogebiete_neu.html) August 18, 2020, we learn that one third of German infections trace back to returning travelers. The majority of these originate from Turkey, Poland, and Spain.

This points to a mis-judgment by ECDC that 3% of infections would stem from returning travelers. In other words, international travel has proven to be a catalyzer for infectious spread throughout Europe.

Some further anecdotal issues:

- In spite of travel restrictions in and out of the European Union, citizens with dual nationality can exercise their right to travel between countries of which they are citizens.

- (Air) travel restriction policies differ widely between countries. This is of particular concern for a country like Belgium, with several well-connected airports just outside of its national borders (CDG, AMS,…).

- Policies for following up travelers returning from red or orange zones, or who have exhibited risky behavior, is partial at best.

Conclusion

(Partially) open border policies, based solely on administrative and legal considerations (e.g., Schengen zone) are epidemiologically detrimental.

It is much more sensible to open borders between countries that are in a very comparable situation (e.g., with a sufficiently low incidence and with a stable or declining trend).

In addition, Europe is an epidemiological patchwork, a situation of which the virus can take advantage, in search of susceptibles and helped by inadequate or even incorrect measures. A more coordinated epidemiological response to the pandemic would be helpful.

There is a chance that a growing number of countries will no longer want to jeopardize their own favorable epidemiological status by opening borders without reasonable restrictions, for example, solely because of the European Treaty (cf. letter by Salla Saastamoinen and Monique Pariat from the DG Justice and Comsumers, August 7, 2020). They may form a subgroup, open to one another, but closed or at least heavily restricted to others.

Maybe this should be seen as an incentive to become part of this growing group of countries, in Europe and beyond, that opt for suppression of the curve. The larger this group becomes, the more the spirit of free movement can be maintained in an epidemiologically sound fashion.